Revolution #92, June 17, 2007

Background to Confrontation:

The U.S. & Iran: A History of Imperialist Domination, Intrigue and Intervention

Part 3: Iran 1953-1979: The Nightmare of U.S. Domination

For over 100 years, the domination of Iran has been deeply woven into the fabric of global imperialism, enforced by the U.S. and other powers through covert intrigues, economic bullying, military assaults, and invasions. This history provides the backdrop for U.S. hostility toward Iran today—including the real threat of war, even nuclear war. Part 1 of this series explored the rivalry between European imperialists, up through World War 1, over who would control Iran and its oil. Part 2 exposed how the U.S. overthrew the nationalist secular government of Mohammed Mossadegh in 1953 and restored its brutal, oppressive, and loyal administrator--the Shah--to power. Part 3 and Part 4 examine what 25 years of U.S. domination under the Shah’s reign meant for Iran and its people, and how it paved the way for the 1979 revolution and the founding of the Islamic Republic.

|

The conventional narrative, repeated at every turn by the government and media, is that what the U.S. does around the world, whether it is economic treaties, political pressure, even war, is aimed at overcoming poverty, tyranny, and oppression, and giving other countries the benefits of democracy, modernization and the “free market.” But what the United States spreads around the world is imperialism and the political structures to enforce that imperialism. And what happened in Iran under the U.S.-installed and backed Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi showed the bitter reality of this truth.

After the 1953 CIA-organized coup, the Shah and the U.S. moved to crush the widespread anti-U.S., anti-Shah opposition, solidify the Shah’s grip on power, and bring Iran firmly under U.S. control--politically, economically, and militarily.

The Shah immediately formed a military government and put Iran under indefinite martial law. The U.S. poured military advisors and aid ($504 million between 1952 and 1961) into Iran, reorganizing, training, and expanding the Monarchy’s police, military and, in 1957, its dreaded secret police--SAVAK.1

Opposition groups which had backed the overthrown Prime Minister Mossadegh, including the broad-based National Front and the pro-Soviet Tudeh Party, were immediately outlawed. All forms of political organization and activity--even literary gatherings--were banned. Massive arrests, unjustified detentions, institutionalized torture, summary tribunals, prison-murders, and executions were the order of the day. Newspapers, magazines, books--even leaflets--were outlawed if they criticized the government or the U.S. Censorship was enforced so strictly that the number of publications soon dropped from 600 under Prime Minister Mossaedegh (1951-53) to around 100.2

Parliament’s limited independence was stripped away, and candidates were now chosen by the regime. A “two-party” system was begun in 1957--with both the “Nationalist Party” and the “People’s Party” initiated and controlled by the Shah. Iran’s educational system was reorganized to institutionalize pro-Shah loyalty and propaganda.

Iran's Oil Economy: “Ownership Without Control”

The U.S. also moved to prop up the Shah by reviving Iran’s economy by integrating it more deeply into the U.S.-dominated world market as a producer of cheap oil, as well as a market for Western goods and investment. Between 1952 and 1961, the U.S. funneled $631 million in economic aid into Iran--the largest amount to any non-NATO country.3 By the 1960s, there were more than 900 U.S. economic and technical experts in Iran. They shaped Iran’s economy, including drafting economic plans and helping create Iran’s leading bank (the Industrial and Mining Development Bank). U.S. direct private investment soared to $200 million, and the U.S. became Iran’s leading trade partner.

Oil revenues still accounted for the bulk of Iran’s exports and state revenues. After the 1953 coup, it would have been politically difficult to go back to the old system of open foreign ownership. Instead, a new agreement was drawn up giving formal ownership of Iran’s oil to the state-owned National Iranian Oil Company (which had been created by Mossadegh) and increasing Iran’s share of the profits to 50 percent. Britain’s monopoly on Iranian oil was broken, and U.S. and other oil giants became part of a new Consortium with exclusive rights to purchase oil from the Shah’s regime.

Behind the scenes, this Consortium was still in charge due to Iran’s dependence on its equipment, technical expertise, and global marketing networks, as well as the Shah’s overall dependence on the U.S. For instance, the eight Consortium members operated under a secret agreement (only revealed in 1974) spelling out the terms on which each would buy Iranian oil and how they would collectively restrict production to avoid a supply glut and decline in profits. Historian Amin Saikal writes, “The international oil companies were placed in such a powerful position that they could run the Iranian oil industry as their interests dictated. They increased and decreased production and prices, and finally controlled supply and demand in markets, to whatever degree and in whatever way suited them best.” Saikal calls this “ownership without control,” which “enabled the consortium to make the real decisions on Iran’s economic growth.”4

Iran lost tens, probably hundreds, of millions as a result. Meanwhile these kinds of arrangements helped Western capital earn an estimated $12.8 billion in profits from Middle Eastern oil between 1948 and 1960.5

The “White Revolution” -- Imperialist Plans, Unintended Consequences

Building Iran’s economy around extracting oil created an island of industrial development linked to global imperialism in a sea of feudalism and small-scale production. In the late 1950s, over 70 percent of the people still lived in rural areas, mostly as tenant farmers or small landholders, mired in poverty. Some 400-450 feudal landlord families (including the Shah’s) owned more than half the land.6 When I visited Iran in 1979 and 1980, Kurdish peasants described being taxed by the village lords for everything from holidays to water, animals, and crops, and being forced to turn over up to 40 percent of their crop. Big landlords had absolute political power in the villages. Peasants had to ask permission to get married or take trips to town. One notorious landlord forced peasants to bring their fiancées to him on the eve of their weddings.

By the early 1960s, the U.S. government was very concerned about the stability of the Shah’s regime (and there was even secret discussion of ousting him). Iran had been hit by runaway prices and food and fuel shortages, and rumblings of discontent were growing louder. Meanwhile, various kinds of nationalist, anti-imperialist revolutions were rippling across the globe--Vietnam, Latin America, Egypt, and Iraq in the 1950s--which were often fueled by peasant struggles for land and liberation from feudalism.

In 1963, the Shah, under the direction of the U.S., embarked on a far-reaching program of economic, political and social reform. Designed by U.S. policymakers and Harvard professors, this so-called White Revolution was a comprehensive imperialist effort to head off upheaval from below, strengthen the Shah’s regime, and turn Iran into a modern, more industrial society with a growing middle class and wider opportunities for foreign capital. Time magazine described this as “a grand design that is intended to wrest Iran from the middle ages into modern industrialized society,” which was realizable thanks to “extensive land reforms and a massive literacy drive,” along with “annual oil royalties worth more than $500 million and an influx of $2 billion in foreign investment capital.”7

In the end, however, the White Revolution helped destabilize Iran and contributed to the situation which led to the Shah being overthrown.

This “revolution” was never intended to mobilize the peasantry or thoroughly uproot feudal relations--economically, politically or socially.8 Large landowners and landlords were ordered to sell land to sharecropping peasants. Coupled with a program of selling state-owned industries to private investors and encouraging capitalist agribusiness and co-operatives, land reform helped “move landlord capital into industry and other urban projects and to lay the basis for a state dominated capitalism in city and countryside,” historian Nikki Keddie writes. It also undercut the political power of feudal landowners, while linking them more closely to a strengthened Monarchy.9

Landlords were entitled to keep at least one-sixth of their land (including their best) and spread their holdings over several villages, so they maintained considerable economic and social power. Only 30 percent of all villages were even covered, and nine years into this “revolution,” only 20 percent of peasant families (700,000 out of 3.5 million) actually received land, often in parcels too small to be viable. Incomes remained abysmally low--80 percent of those in rural areas received a mere $200 or less a year in 1972.

Roughly 40 percent of Iran's villagers were landless laborers who didn’t benefit from the "land reform" at all. Nearly 600,000 families were forced to leave the land and migrate to urban areas, contributing to a huge swell in Iran’s urban population during the 1960s and 1970s.

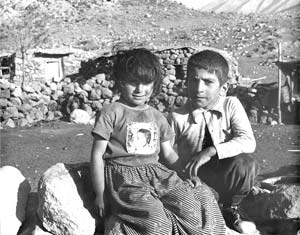

Areas like Kurdistan, which suffered intense national oppression, were barely touched by the White Revolution. Some 80 percent of the people still lived in villages. In the mid-1960s, more than half of Kurdish families (on average five to six people) lived in a single room. Most of their dwellings had neither electricity nor running water.10 This was still largely the situation when I visited after the 1979 revolution. Many villages had no running water, electricity, schools, or hospitals. One farmer told me, “Many are unemployed, none of us can rely on one piece of land; it’s too small and poor and we have too few animals. One has to try to get two or three jobs to eat and not to die.” Another commented, “We have nothing here, no jobs and no schools, no electricity and no hospitals--no life and no future.”

Land reform, granting women the vote, and opening Iran up to greater foreign influence drove important segments of the Islamic clergy to vocally oppose the White Revolution. Iran’s clerics had long been part of the feudal order and establishment, and had joined popular struggles against foreign imperialism and its client monarchs when they feared that Islam, traditional feudal social relations, and the role of the clergy were being undercut. Some leading clerics were big landowners and the clergy overall drew much of its financial support from religious endowments based on land ownership.

In 1963, riots broke out in Qom and Tehran after Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini had been placed under house arrest for speaking out against the White Revolution. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, were shot by the Shah’s troops. The next year, after Khomeini publicly denounced the granting of legal immunity for all U.S. government personnel in Iran, Khomeini was forced into exile in Najaf, Iraq. But through these events, Khomeini emerged as a leading cleric and opponent of the Shah, who would return 16 years later, after the Shah’s overthrow, to found Iran’s first Islamic Republic.11

Next: Part 4 - Iran in the 1970s: Oil Boom and Seething Discontent

Footnotes

1. Ali Reza Nobari, ed., Iran Erupts, p. 143; Ali M. Ansari, Confronting Iran, p. 41. [back]

2. Nobari, p. 64. [back]

3. Ansari, p. 41. [back]

4. Amin Saikal, The Rise and Fall of the Shah, pp. 50-51. [back]

5. Larry Everest, Oil, Power & Empire--Iraq and the U.S. Global Agenda, pp. 57-58. [back]

6. Fred Halliday, Iran: Dictatorship and Development, pp. 106-07, 110. [back]

7. Time, Feb. 11, 1966. [back]

8. Nikki Keddie, Modern Iran: Roots and Results of Revolution, p. 144; Ansari, p. 46. [back]

9. Keddie, p. 145. [back]

10. Gerard Chaliand, ed., A People Without a Country: The Kurds and Kurdistan, p. 113. [back]

11. Ansari, p. 49; Dilip Hiro, Iran Under the Ayatollahs, p. 47. [back]

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.