Revolution #150, December 14, 2008

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China (1966-1976)

|

Photo: asiasociety.org/chinarevo |

![]() For hundreds of years colonial foreign powers invaded and divided up China. Most people in China were landless peasants, forced to work for big landlords. They faced constant debt, poverty, starvation, and disease. Families sold their children because they couldn’t feed them. In the city of Shanghai as many as 25,000 dead bodies were picked up off the streets each year. Hundreds of thousands were rounded up and forced to work as indentured laborers on plantations and in mines all over the world. The British flooded China with opium, turning over 60 million Chinese people into addicts—while foreign capitalists got rich off this drug trade.

For hundreds of years colonial foreign powers invaded and divided up China. Most people in China were landless peasants, forced to work for big landlords. They faced constant debt, poverty, starvation, and disease. Families sold their children because they couldn’t feed them. In the city of Shanghai as many as 25,000 dead bodies were picked up off the streets each year. Hundreds of thousands were rounded up and forced to work as indentured laborers on plantations and in mines all over the world. The British flooded China with opium, turning over 60 million Chinese people into addicts—while foreign capitalists got rich off this drug trade.

Mao Tsetung and the Communist Party of China led the Chinese people in 20 years of armed struggle against all this. In 1949 the revolution seized power. Foreign colonialism was kicked out. Feudal landlords and big-time capitalists were overthrown. A new socialist government was established.

![]() Under socialism people’s lives were immediately and dramatically improved. New laws banned arranged (forced) marriages, selling children, child labor, and drug trafficking. Literacy campaigns were launched. Mass organizations of peasants, youth, women, workers, intellectuals, and professionals were formed. Millions participated in figuring out and carrying out revolutionary transformations in every sphere of life. Farming and factories were organized in ways that narrowed inequalities between the city and countryside, between workers and peasants, between men and women, and between mental and manual labor. By the early 1960s there were communes in the countryside, averaging 20,000 people. Cooperative community dining rooms, nurseries, and amateur theater groups were organized. Between 1949 and 1975, life expectancy in socialist China more than doubled, from about 32 to 65 years.

Under socialism people’s lives were immediately and dramatically improved. New laws banned arranged (forced) marriages, selling children, child labor, and drug trafficking. Literacy campaigns were launched. Mass organizations of peasants, youth, women, workers, intellectuals, and professionals were formed. Millions participated in figuring out and carrying out revolutionary transformations in every sphere of life. Farming and factories were organized in ways that narrowed inequalities between the city and countryside, between workers and peasants, between men and women, and between mental and manual labor. By the early 1960s there were communes in the countryside, averaging 20,000 people. Cooperative community dining rooms, nurseries, and amateur theater groups were organized. Between 1949 and 1975, life expectancy in socialist China more than doubled, from about 32 to 65 years.

|

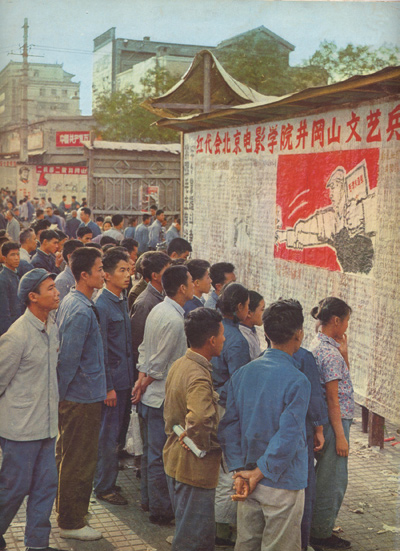

“Big-character posters” were handwritten posters that went up on the walls of schools, factories, and neighborhoods all over China during the Cultural Revolution. They were an incredible expression of public criticism of policies and leaders. Accessible to everyone, they gave an immediate platform for mass debate on a grand scale. |

![]() Mao’s vision of socialism went beyond just giving people food, clothing and basic rights. Building socialism in China meant continually digging away at and transforming old economic and social ways of doing things and relations between people. It meant getting rid of old and oppressive ways of thinking that go along with all this. It meant moving toward a communist world free of classes, oppression, and exploitation.

Mao’s vision of socialism went beyond just giving people food, clothing and basic rights. Building socialism in China meant continually digging away at and transforming old economic and social ways of doing things and relations between people. It meant getting rid of old and oppressive ways of thinking that go along with all this. It meant moving toward a communist world free of classes, oppression, and exploitation.

But some leaders in the Communist Party wanted to take China in the opposite direction. They had fought in the revolution, wanting to get rid of foreign domination and liberate China. But their sights went no further than building China into a powerful nation. They promoted programs and policies that reinforced oppressive capitalist relations and thinking. This is why Mao called them “capitalist roaders.”

By the mid-1960s, the whole future of socialist China was in danger. Mao made the pathbreaking analysis that classes and class struggle continue under socialism. There is real struggle over what kind of society to build—capitalist or socialist. And the biggest danger was top leaders in the communist party and government who wanted to bring back capitalism. But Mao recognized that just removing such leaders wouldn’t solve the problem. He searched for a way to prevent the revolution from getting turned back—“a form, a method, to arouse the broad masses to expose our dark aspects from below.”

|

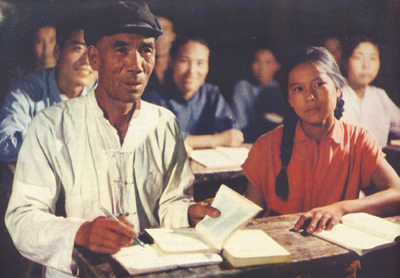

The goal of closing the gap between city and countryside, worker and peasant, men and women, included a literacy campaign. Here young and old alike learn to read and write by studying political works in an evening school set up in the village of Hsiaochinchuang. |

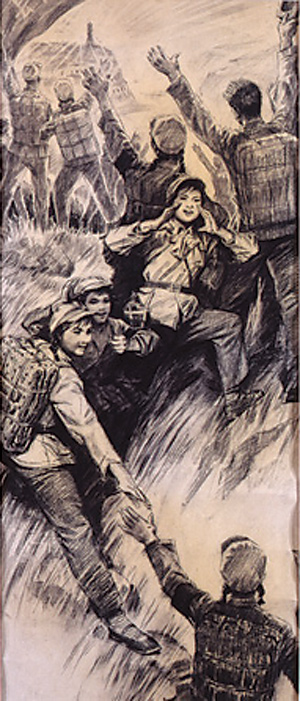

![]() In 1966 Mao launched the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution—a “revolution within the revolution.” Hundreds of millions were unleashed to discuss, debate, and take responsibility for the direction and fate of society. Students criticized oppressive educational and political authority. Peasant women confronted feudal tradition. Workers rose up against conservative party leaders. Intellectuals, artists, and professionals dedicated their lives to “serving the people.”

In 1966 Mao launched the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution—a “revolution within the revolution.” Hundreds of millions were unleashed to discuss, debate, and take responsibility for the direction and fate of society. Students criticized oppressive educational and political authority. Peasant women confronted feudal tradition. Workers rose up against conservative party leaders. Intellectuals, artists, and professionals dedicated their lives to “serving the people.”

|

During the Cultural Revolution, over a million young peasants and urban youth received basic medical training and brought much-needed health care to the masses in the countryside. These “barefoot doctors” lived and worked among the common people, including working barefoot in the fields. They were one of the key reasons why life expectancy in China doubled from 32 years in 1949 to 65 years by 1976. |

![]() Mao pointed out: The target of the Cultural Revolution was “those persons in authority taking the capitalist road.” But the strategic aim was “to solve the problem of world outlook”—for the masses to transform their world outlook and transform society, all toward the goal of a communist world.

Mao pointed out: The target of the Cultural Revolution was “those persons in authority taking the capitalist road.” But the strategic aim was “to solve the problem of world outlook”—for the masses to transform their world outlook and transform society, all toward the goal of a communist world.

The Cultural Revolution brought about real achievements in health care, education, and science. Real advances were made in the struggle against the oppression of women and minority nationalities. A whole new revolutionary culture developed. Economic and social relations were revolutionized. Old and oppressive ways of thinking were challenged and transformed.

![]() When Mao died in 1976, “capitalist roaders” in the Chinese Communist Party seized power. They arrested hundreds of thousands and killed thousands. They overthrew socialism and restored capitalism.

When Mao died in 1976, “capitalist roaders” in the Chinese Communist Party seized power. They arrested hundreds of thousands and killed thousands. They overthrew socialism and restored capitalism.

Today China continues to call itself socialist and communist. But it has been a capitalist country for over 30 years. This has meant suffering and misery for the masses of people. China is once again dominated by imperialism, capitalist exploitation, and backward feudal oppression. There is extreme economic and social polarization—between rich and poor; between men and women; between those in the cities and those in the countryside; between mental and manual labor.

The lesson to draw from all this is NOT that socialism is impossible. The revolution did not fail, it was defeated.

|

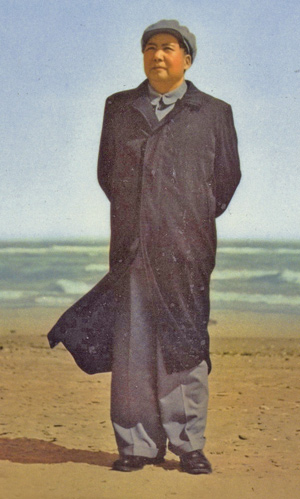

Mao Tsetung in the 1960s. |

![]() Bob Avakian has stood out in defending the tremendous achievements of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, and deeply analyzing the lessons of this whole experience. On this basis, he has further developed the science of communism in many dimensions. As a crucial part of that, he has gone further in developing the vision of a future, emancipatory society and has analyzed more deeply the means to get there—the socialist transition period of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Bob Avakian has stood out in defending the tremendous achievements of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, and deeply analyzing the lessons of this whole experience. On this basis, he has further developed the science of communism in many dimensions. As a crucial part of that, he has gone further in developing the vision of a future, emancipatory society and has analyzed more deeply the means to get there—the socialist transition period of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

The recent manifesto from the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA, Communism: The Beginning of a New Stage, puts it this way: “While deeply immersing himself in, learning from, firmly upholding, and propagating Mao’s great insights into the nature of socialist society as a transition to communism—and the contradictions and struggles which mark this transition and whose resolution, in one or another direction, are decisive in terms of whether the advance is carried forward to communism, or things are dragged backward to capitalism—Bob Avakian has recognized and emphasized the need for a greater role for dissent, a greater fostering of intellectual ferment, and more scope for initiative and creativity in the arts in socialist society.” This new synthesis has put the communist revolution back on the scene; everyone and anyone who yearns for a better, truly liberated future needs to deeply get into this further advance of communism.

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.