Vietnam War Protesters Have NOTHING to Apologize For

When patriotism and pro-war become synonymous.

by David Zeiger

October 2, 2017 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

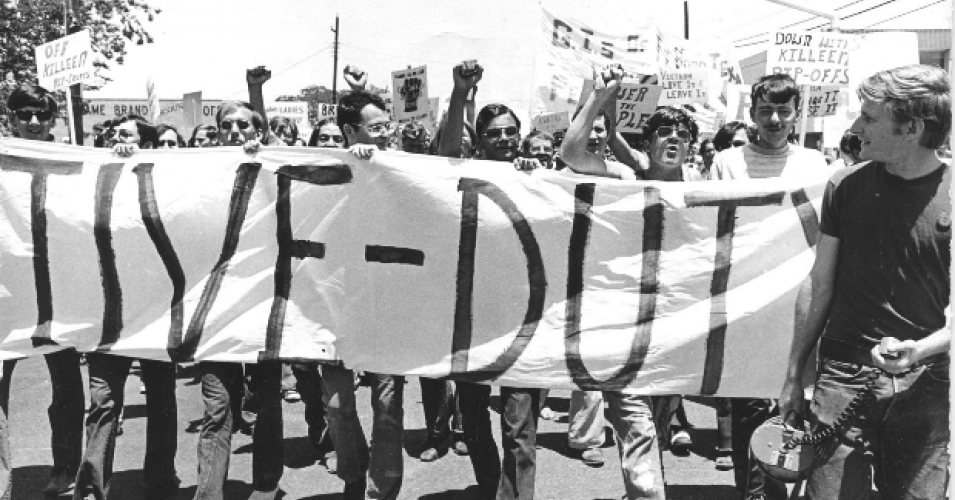

Author David Zeiger with active duty GIs demonstrating on Armed Forces Day, 1971

The following article first appeared online at CommonDreams.org and is republished here. David Zeiger is an award-winning filmmaker and creator of Sir! No Sir!, a documentary about the GI resistance during the Vietnam War. Zeiger is an initiator of Refuse Fascism. This article refers to the documentary The Vietnam War by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, which PBS just finished running as a series. Revcom.us will have more on that film in the near future.—Revcom editors

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 License

How many times have you heard, or even said yourself, something like this:

It was beyond cruel what was done to Viet Nam vets. I protested the war but not the soldiers who’d been thru hell.

That’s a comment made on my Facebook page when I posted Jerry Lembcke’s very insightful review of Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s series, The Vietnam War. Lembcke points out that the series promotes the established narrative that for Vietnam vets, the experience of coming home to a “hostile” public was “more traumatic than the war itself.” As I will discuss here, Lembcke, a Vietnam veteran and Associate Professor Emeritus at Holy Cross College, has dedicated much of his life to countering and disproving that narrative.

Now take a close look at the above statement. I protested the war but not the soldiers who’d been thru hell. The implication is, of course, that while this person didn’t do it, others must have “protested the soldiers,” referring to the ubiquitous stories of soldiers and veterans being harassed, hounded, called baby killers and spat on by a variety of protesters and, as the stories usually go, “long haired hippies.” Actually, this particular comment was part of a string of responses to someone who claimed he was “urinated on while in uniform.”

That the returning Vietnam veterans were “spat on and called baby killers” has now reached the level of gospel truth, most distressingly among those who were themselves part of the very movement being vilified by those claims. No one saw or was a party to such attacks, yet everyone “knows” it happened. Someone must have done it, or why would so many people claim it was done to them?

Why indeed. Answering that one question sheds a lot of light on how and why the relationship between the antiwar movement and the veterans of that war has been widely, and very effectively, rewritten—a rewrite that has gone virtually unchallenged by those who were there and who, frankly, know better. Today, four generations after the Vietnam War, the mythology of mistreated veterans continues to play a profoundly powerful role in stifling protest against America’s wars in the name of “supporting the troops.” And with Donald Trump threatening to “Completely destroy North Korea” while unleashing the military in the Middle East, nothing could be more urgent than confronting that myth.

First, some personal background. From 1970 to 1972, I was on the staff of the Oleo Strut, a GI Coffeehouse in Killeen, Texas, just outside of Ft. Hood, home to tens of thousands of Vietnam returnees who still had six months or more left to serve. The Oleo Strut, like dozens of GI coffeehouses near bases around the country, was a place where soldiers could find literature about the antiwar and Third World liberation movements, discuss and debate the war with both civilians and fellow GIs, and, most significantly, build their own movement against the war and the military. For two years I helped them distribute their underground paper, The Fatigue Press, with a monthly press run of 5,000. In 1971, I helped plan and organize an “Armed Farces Day” demonstration against the war right outside the gates of Ft. Hood that over two thousand GIs participated in.

Statistics and a wealth of documentary evidence from that time show that my experience at Ft. Hood was the norm, not the exception. The GI Movement of 1968-1973 was so all-pervasive that Col. Robert Heinl famously wrote that it had “infected the entire armed services.” Historian James Lewes has documented over 500 different GI underground newspapers (available online at the Wisconsin Historical Society), along with dozens of organizations from GIs United Against the War to clandestine Black Panther chapters in the military. A 1972 study commissioned by the Department of Defense found that 51% of all troops in Vietnam had engaged in “some form of protest,” from wearing a peace sign on uniforms, to desertion (over 500,000 “Incidents of desertion” in the course of the war), demonstrations, and outright mutiny (including the widespread practice of “fragging”—troops killing their own officers). And by 1972 Vietnam Veterans Against the War was a highly visible, major force across the country. The widespread picture of a military full of soldiers “doing their duty” while privileged civilians protested and hurled insults at them is, to put it bluntly, a lie.

In 2005, at the height of the Iraq war, I made the film Sir! No Sir! That film, broadcast in over 200 countries around the world, told the story of the GI Movement, a story that had been erased from just about every history of the Vietnam War. In Sir! No Sir!, Jerry Lembcke makes the point that the reality of thousands of GIs and veterans opposing the war had been replaced by the myth of hippies spitting on them, and it was that contention that drew the ire and attacks from pro-war veterans who hounded several critics who had praised the film.

But Lembcke is the only person I am aware of who has thoroughly researched the claims of veterans being spat on and the broader insistence that they were shunned and attacked by the antiwar movement. He wrote about his findings in his 1998 book, The Spitting Image: Myth, Memory, and the Legacy of Vietnam, a must-read for everyone who wants to know how veterans were actually treated by the antiwar movement. Here are just a few tidbits of what his research revealed.

To begin with, over the entire course of the war there is not a shred of documentary evidence that any spitting incidents occurred. No articles in newspapers or magazines, no letters to the editor, no television news stories, no FBI reports, no arrests or complaints filed with police. Nothing. Not even Stars and Stripes, voice of the military, reported on any spitting incidents. And in an era that was heavily documented with photographs, including by the GIs themselves (Lembcke points out that Pentax cameras were sold at PXs and were the camera of choice among the troops, not unlike cell phones today), not one photo of a veteran being spat on exists.

The stories that are told almost always happen in public, usually at airports and coming from crowds of demonstrators whose goal is to humiliate the returning troops. We are told that commanding officers warned GIs they’d be spat on when they returned home, that they should throw away their uniform to protect themselves. Yet no one alerted the cops, or military authorities, or the press? We’re talking about assault here. Wouldn’t the FBI, whose goal throughout the nineteen sixties was to thwart and undermine the antiwar movement, have arrested at least one spitter? There were, if the stories are to be believed, hundreds—even thousands—of them. And what about the press? Soldiers at airports being routinely abused and spat on would certainly have gotten to the media, who would, as Lembcke points out, “been camping in the lobby of the San Francisco airport, cameras in hand, just waiting for a chance to record the real thing—if, that is, they had any reason to believe that such incidents might occur.”

The simple fact is that between 1965 and 1975 no one was claiming to have been spat on. Okay, so maybe they were spat on metaphorically, as the increasingly popular expression goes. I have seen several people who initially claim they were spat on, when challenged, change the story to a version of “Well, I wasn’t literally spat on, but I may as well have been.” When the gentleman who claimed on my Facebook post to have been urinated on was challenged by several people, his story became “I ducked into a bar to get away from the jerks.” Who the “jerks” were was never explained.

But again, that’s not what vets were saying back in the day. As Lembcke writes, “A U.S. Senate study, based on data collected in August 1971 by Harris Associates, found that 75 percent of Vietnam era veterans polled disagreed with the statement, ‘Those people at home who opposed the Vietnam War often blame veterans for our involvement there.’ Ninety-nine percent of the veterans polled described their reception by close friends and family as friendly, while 94 percent said their reception by people their own age who had not served in the armed forces was friendly. Only 3 percent of returning veterans described their reception as ‘not at all friendly.’” (Emphasis added)

And just like the spitting stories, there is no documentary evidence of antiwar activists screaming “baby killer!” at soldiers and veterans. In fact, as every activist who looks honestly at their history can attest, it was the government and military machine that was consistently targeted, not the soldiers. “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?!” was one of the most popular chants, until it was Richard Nixon doing the killing.

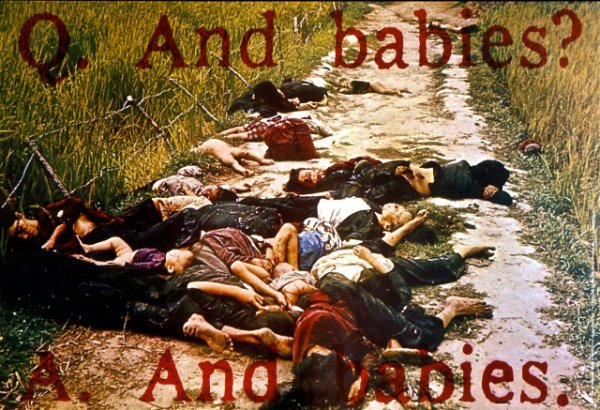

So where did this idea of vets being called “baby killer” come from? A plausible source is the My Lai massacre poster. In March of 1968, over 500 unarmed civilians—men, women, and children—were systematically gunned down by a company of GIs in the 23rd (Americal) Infantry Division. The military covered up the My Lai massacre for over a year until it was exposed by journalist Seymour Hersh. Caught in their cover-up, the military indicted 22 soldiers and Lt. Calley, the officer on the scene, for the murders. It was the military, not the movement, who “blamed the troops” when the results of their murderous policies were exposed.

In the wake of My Lai, the poster produced by the antiwar movement featured a horrific photograph of bodies piled up in the village. There were only two lines of text: “And babies? And babies.”

I know this powerful poster well because we had it in the Oleo Strut and reproduced it in the Fatigue Press to be seen by thousands of soldiers. Why? Because it embodied the criminal nature of the war they were forced to fight. I imagine some people took it personally, but it should go without saying that the intent was never to accuse all soldiers of being baby killers, but to confront them with the hard reality of the war and bring them into the movement. Should we, in the name of “Honoring the troops,” not have exposed and condemned the My Lai massacre?

Were there angry debates about the war, from dinner tables to street corners to campuses? Absolutely. Were there demonstrations outside military bases, as the purveyors of spitting stories complain about? Of course—but, as in my own experience, those demonstrations were more often than not led by veterans and active duty soldiers who targeted the government, not their fellow GIs. Did antiwar activists argue with everyone, including veterans, that the United States was engaged in a criminal, genocidal invasion that targeted civilians? Most definitely, as well they should have. Did those arguments at times get more than a bit personal (“You support genocide!”)? Yes they did, and understandably so. That was the nature of the times, and the urgency of ending the slaughter that was the Vietnam War.

In one report I read recently, a veteran described how isolated and uncomfortable he felt at the college he attended. He couldn’t express his opinions in discussions about Vietnam, despite his service. It turns out the college he attended was Berkeley, and he supported the war. I was struck by this, because anyone who openly supported the war at Berkeley was bound to be verbally pummeled. It would be kind of like advocating slavery at an NAACP convention. But his discomfort most likely had nothing to do with the fact that he was a veteran, it was his support for the war that was under attack.

And that’s exactly the point. The debate in society was about the war, and veterans were as much a part of that debate as everyone else, if not more so. Veterans were not a monolithic group. Those who opposed the war, and there were thousands, were welcomed with open arms by the antiwar movement, becoming a leading force in the country as Vietnam Veterans Against the War. It was veterans, particularly in VVAW, who exposed most vividly the policies of the government and military—carpet bombing, free fire zones, body count, and the unprecedented use of napalm and Agent Orange. These were the official weapons and strategies employed by the U.S. in Vietnam. And it was those strategies that made Vietnam a genocidal war filled with the atrocities so vehemently, and rightly, denounced by the antiwar movement.

So what happened? How did “The reception from my peers was friendly” get turned into “I was spat on and traumatized?” This is the heart of the matter, and the question Lembcke devotes most of his book to answering. The short answer is that it was the result of a highly effective, decades long campaign by many forces in society bent on casting blame for America’s defeat in the war not on the government and the nature of the war itself, but on the supposed “betrayal” of the soldiers by the antiwar movement. By turning veterans into victims of angry mobs of protesters, those seeking more wars of conquest hoped to isolate and suppress any opposition in the name of “Supporting the troops.” And no one did more to advance that cause than Ronald Reagan.

Although the charge against the antiwar movement of “Disloyalty to the troops” was pushed by Richard Nixon as early as 1969, the spitting stories didn’t fully emerge until the mid-1980s, fifteen years after the war, which is itself strong evidence of their mythical nature. Most significantly, they sprang up while the Reagan administration was secretly funding reactionary armies in Latin America and railing against what he called the “Vietnam Syndrome”—the reluctance of most Americans to support sending troops into Third World countries. Shaming the antiwar movement was key to that campaign, and the spitting stories, eagerly told by a handful of pro-war veterans (the 3 percent of the above survey), did the trick.

Hollywood did their part as well, producing a wave of fantasy revenge films starting in the late seventies. Top of the heap was Sylvester Stallone’s wildly popular First Blood (1982) and Rambo: First Blood II (1985), in which a bulked-up, testosterone-filled caricature of a Vietnam vet single-handedly takes out his revenge first on an uncaring America, then on the bloodthirsty Vietnamese. First Blood featured the absurd scenario of Rambo, a former Green Beret and highly trained killer, whining that “hippies” spat on him at an airport. Those hippies sure were a powerful bunch!

The spitting stories hit their zenith when America did send large numbers of troops overseas, to the Middle East, for the first Gulf war in 1990. Iraq had occupied Kuwait, claiming it was part of their territory (Kuwait’s borders had been created by British colonialists in the early Twentieth Century). As the first Bush administration was flailing around looking for a justification to invade, huge demonstrations were held across the country demanding no invasion. But once the troops were sent, the media was filled with stories of young boys fearful—not of facing battle, but of the folks back home. Once again, horror stories were spread about the treatment of Vietnam vets, along with dire warnings, including from protest leaders, to not repeat the “mistakes” of the nineteen sixties. Congressman John Murtha visited the troops in the Gulf and reported in the New York Times that troops repeatedly asked him whether the “folks back home” supported them. “The aura of Vietnam hangs over these kids,” he said. “Their parents were in it. They’ve seen all these movies. They worry, they wonder.” With that, the “reason” for the war became supporting “our boys in harm’s way.” The demonstrations evaporated, replaced by yellow ribbons.

And that, of course, has both continued and intensified to this day. I’m a baseball fan, and every Dodgers game I attend includes a “Salute to a hero” ceremony, with thousands of fans standing and cheering as the veteran’s deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan are ticked off. You have to be blind to not see that, in the name of “honoring” this individual, it is the wars themselves that are being cheered. But woe to anyone who would actually say that. It’s okay to oppose those wars, as long as you are very careful to never imply that soldiers are committing war crimes and always say “Thank you for your service.” Is it surprising in this atmosphere that there is, today, no antiwar movement?

As the saying goes, a lie repeated often enough becomes the “truth.” The Burns/Novick Vietnam War series ends with Nancy Biberman, [who had been] a Columbia University student activist, asking forgiveness for calling veterans “baby killers.” I’ll go out on a limb and say that Ms. Biberman never called veterans baby killers. Maybe she now believes that even mentioning the thousands of civilians killed by U.S. forces in Vietnam is tantamount to doing just that. Maybe she thinks that others must have done those horrible things we have heard about and every antiwar activist should now atone for their sins.

Both are a surrender to the lie. And both are, despite intentions, an open door to more wars and more slaughter.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.